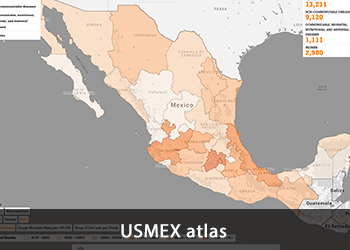

The Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies (USMEX) has undertaken a multi-year project to map health outcomes in Mexico, with a focus on health at the state and municipal level. Launched in 2010 with support from the Hewlett Foundation, the Center’s Atlas of Public Health in Mexico and brand new municipal health scorecards were presented at an open data conference in Mexico City earlier this fall.

USMEX Associate Director Melissa Floca made the presentation at the Regional Conference on Open Data in Latin American and the Caribbean, which brought together academics, governments, businesses and civil-society organizations to share their work and experiences. The conference is considered the most important regional event on open data in the region.

“The conference brought together a diverse and exciting group of speakers and the energy in the room was impressive,” Floca said. “It was inspiring to learn about the work being undertaken throughout Latin America to use open data to improve policy and welfare.”

Using data proactively

Newly revised with complete, interactive maps, the USMEX atlas uses data from death registrations made public by the Mexican government on a yearly basis. The data includes cause of death, gender, education level and location of death at the individual level, along with other valuable demographic information that provides insight into the patterns, causes and affects of health at the local level.

USMEX’s first step was to reclassify the cause of death listed on each registry — which numbered upwards of seven thousand different causes — into the World Health Organization’s more streamlined Global Burden of Disease classification.

“This data provides valuable insight into the patterns of health in Mexico at the local and individual level, enabling researchers to examine the intersection of health with economic growth, demographic change, the extension of health infrastructure and insurance coverage, and electoral competiveness,” Floca said.

The research — headed by former USMEX director and current Stanford University professor Alberto Diaz-Cayeros and supported by Floca and USMEX fellow Micah Gell-Redman — takes the newly classified causes of death and creates geographic information system, or GIS, mapping of these variables. Data is categorized by year from 1998 to 2012.

Another important contribution of the USMEX research team was the calculation of “years of life lost” for specific diseases. To do this, they calculated the life expectancy for each death certificate based on the year, gender and age at time of death. For example, if someone dies at age 40 and their life expectancy is 80, they have lost 40 years of life. This calculation provides a clearer understanding of the human cost of death for specific diseases that provides an additional lens beyond the more common statistic of mortality rates.

“It is important to understand that the average years of life lost per death in traffic accidents is 39,” Floca said. “That data point provides context for understanding the public health challenge.”

The purpose of the project is two-fold: to provide a citizen-based approach in looking at local health outcomes and a platform for further research. Results are made available to the public through interactive maps, downloadable data sets on health outcomes and local-level scorecards.

Keeping score

Released soon, the project’s scorecards synthesize the complex data into easy-to-use graphs and charts, explaining cause of death and years of life lost at the local level and providing analysis on how health outcomes in one place compare to national and state norms. They created scorecards for all 32 Mexican states as well as the 250 largest municipalities.

“Deaths and years of life lost are standardized and comparable across locations,” Floca said. Additional information on the scorecard includes the number of clinics, doctors and doctor visits in the region, along with the penetration of insurance coverage.

“This is meant to be used as a tool for citizens to understand the health outcomes where they live. If you’re a citizen and you want to know what’s going on in your area, this is the only way you’ll know,” Floca said. “It’s also designed to be used by policy makers and health practitioners to identify places where things are going right and where things are going wrong.”

Though this marks the end of the larger data collection phase of the project, Floca said making the data available means the next step can be done by just about anyone: empirical research by individual scholars, nonprofits and government organizations that could lead to policy evaluations and even concrete recommendations, helping to improve the health of people across the country.

“Now, anyone can track health outcomes at the municipal level, and policy makers should look carefully at the differences across geographies and time, as well as specific demographics,” Floca said. “This way, they can understand who is at risk and craft policies to make change.”

Visit the Atlas of Public Health in Mexico website to interact with the data and learn more about the Center’s work.